Small transnational cinema from a risk environment

The recent history of Lithuanian documentary can illustrate how this genre could develop in a small film ecosystem in a relatively short time after hard transitional periods in the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s: progress was due to positive political stimulus, increased internationalization and bigger tolerance for creative risk and new ideas. Lithuanian cinema is a cinema of a small country/nation, considering the four measures singled out by Mette Hjort: “population, geographical scale or territory, and gross national product or per capita income” as well as “(a history of) rule by non-co-nationals over a significant period of time” (Hjort 2015, 50). The last criterion is rarely applied, still, considering the dimensions of the country and its political, economic and cultural weight in the region, the continent and the world, “it is an important one”, as Hjort argues, “because it brings some of the challenges, associated with filmmaking in postcolonial contexts, as well as in contexts where people strive after an independent state, into the picture” (Hjort 2015, 50). Lithuania is obviously one of the smallest countries in Europe and in the world, with a population of just 2.79 million, [1] whose language is spoken by about 4 million people locally and globally. The GDP of the country is 48.7 billion EUR, which was among the smallest in the EU in 2020. [2] In addition, its history includes long periods of being overruled by its bigger neighbours, [3] as well as cultural and economic isolation – all of which had a strong impact on national welfare and progress in all fields, including film. Therefore, Lithuanian cinema has been facing “systematic risks” and “contradictory forces” common for many countries of small economies and post-colonial histories, such as “neo-liberal economic and political pressure of globalization into a greater dependency on external markets” and “a strong vested interest in nation building and the maintenance of a strong sense of national identity relevant both internally and externally to the nation.” (Hjort and Petrie 2007,15) According to Hjort, “systematic risks would be those that arise from specific measures of size and permeate the entire filmmaking milieu, with potential implications for all who contribute to the filmmaking effort” (Hjort 2015, 51).

In this article I will focus only on the post-1990 context, in order to discuss the circumstances in which new generations of documentary filmmakers emerged and explain the way their films relate to major political and economic transformations and transitions, local filmmaking tradition and global trends in the documentary genre. I will also glimpse into the major risks and challenges for filmmakers who work in a small country, in the minor genre of creative documentary. [4] Mette Hjort claims “that risk is absolutely central to film” (Hjort 2012, 4), and “that risk is not simply a matter of concern, but also a phenomenon that can be selectively affirmed as source of opportunities for small-nation film practitioners” (Hjort 2015, 58). I find these claims absolutely convincing, and will rely on this approach to understand the concept of risk as it is developed in her book Film and Risk (Hjort 2012) and an article entitled “The Risk Environment of Small-Nation Filmmaking” (Hjort 2015). I relate filmmaking risks primarily to the local and global economy of film; the filmmaker’s identity (gender, age, nationality, education); as well as film style and approaches to topics of local and global relevance. I assume that the look into how film policy makers redefine and reduce the economic risks of national film industry and how film community tolerate different types of risks is central for the discussion of the emergence of new generations of documentarists and the formation of new trends in documentary filmmaking.

The 1990s and the 2000s were marked with positive changes in the global documentary film ecosystem and the growth of prestige and popularity of the genre. A good example for these changes was Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11, which won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 2004 and grossed 119 million USD on the USA market alone. As Patricia Aufderheide noted, “in the 1990s documentaries began to be big business worldwide, and by 2004 the worldwide business in television documentary alone added up to 4.5 billion US Dollar revenues annually. (…) Theatrical revenues multiplied at the beginning of the twenty-first century. DVD sales, video-on-demand, and rentals of documentaries became big business. (…) Markets who had discreetly hidden the fact that their films were documentaries were now proudly calling such works ‘docs’” (Aufderheide 2007). In Europe, support for documentary film was growing as well. In the 1990s the European Union’s MEDIA programme was launched, which offered new financing, distribution and networking possibilities for creative documentary makers. In the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s documentary film festivals were booming – the Sheffield International Documentary Festival, the DocPoint Helsinki Documentary Film Festival, the Copenhagen International Documentary Festival, the Doclisboa International Film Festival, the Vilnius Documentary Film Festival and many others were founded. World Film Market Trends observations done by the European Audiovisual Observatory in 2004-2006 revealed an obvious increase in documentary film production and distribution in France, Germany, Denmark and some other countries. [5] In this period documentary film was fully acknowledged and institutionalized, and the visibility of documentarists increased.

In Lithuania, however, the situation of the documentary sector was less than ideal. The first two decades after the reestablishment of independence in 1991 were unfavourable both for the emergence of new documentary film talents, and the maintenance of the profession for those who already had established careers. “The spectacular collapse of Soviet Union”, as Laura Lapinske put it, was tailed by the “immediate restructuring of major industries, the initiation of land reforms and privatization of state property” (Lapinske 2018, 67). The film industry was strongly affected by the “post-Communist transformation”, which occurred in 1991–1995/1996, a period of “extraordinary politics” and “radical reforms” (Lauristin, Norkus, Vihalemm 2011, 129). The film community in Lithuania and the entire post-socialist block was coping with economic bankruptcy and cultural agony. “Earlier concerns over freedom of expression rapidly vanished,” as Dina Iordanova aptly pointed out, “taken over by worries over the emerging constraints of the market economy” (Iordanova 2003, 143). In that period the Lithuanian gross domestic product was very modest. In 1991 GDP was just 415 million Litas (approximately 120 million Euros), in 1995 – 24 103 billion Litas (approximately 7 billion Euros) and in 2001 – 47 968 billion Litas (approximately 13.9 billion Euros). [6] These circumstances had a long term effect on film industry and community because, as Hjort argues, “the gross domestic product has clear implications for the kinds of institutions that can be built, the kind of equipment that can be made available to filmmakers, the stories of budgets that filmmakers and those who market their films have to work with, the frequency with which film professionals are able to practice their craft, and a nation’s capacity to defend its language (or languages) and cultural values from the effects of various profit driven ventures mounted by companies linked to large nations” (Hjort 2015, 51).

The Lithuanian film industry was stagnating for more than a decade due to the severe economic conditions, modest government subsidies, the privatization of film infrastructure (studios, cinemas, etc.) and small private investments in new infrastructure and film production. Only few filmmakers, who debuted towards the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, such as Šarūnas Bartas, Arūnas Matelis, Audrius Stonys and Valdas Navasaitis, were able to produce films on a relatively regular basis (mainly with private and international support), to develop distinctive styles, and even achieve international successes. These artists where associated with Kinema studio, the first private film studio founded in 1989 by Bartas in Vilnius [7]. Their artistic success proved that “there are strong links between highly valued phenomenon such as creativity and risk taking” (Hjort 2012, 22). Other filmmakers could release just one or two shorts, as the average number of annual documentary premieres in that period ranged from 7 to 15. [8] The production of national films became too risky business as the Government could not, in Hjort words, “shifting some of the costs, and thereby some of the risks, of filmmaking from the private sector to the public sector” and thus sustaining national culture (Hjort 2012, 12-13). The agony of the state-owned film distribution enterprise “Lietuvos kinas” and the collapse of the regional exhibition network led to a situation where national film premieres where held primarily for the film community in Vilnius, and lost connection with local audiences at least for a decade. In Lithuania, like in other Eastern European counties, “most of the new private distributors who emerged subsequently chose to strictly abide by market rules and to work with Hollywood box-office winners rather than play the losing card of domestic ones …” (Iordanova 1999, 46).

Even joining The MEDIA Programme of the European Union in 2003, and four years later the membership at Eurimages [9] did not bring a sudden positive effect on the Lithuanian film sector. It took several years for producers and directors to learn how to make a successful application and get projects funded, co-produce with professionals from different film cultures and economies, and develop international professional networks. The situation of the film industry improved significantly once a new governmental body, the Lithuanian Film Centre was established in 2012, in charge of film policy and industry, advocating the need to increase budgetary subsidies to the national film sector. It modelled on European film institutions, whose purpose, according to Hjort, is to facilitate “risk avoidance, a reduction of risk, or a transfer of risk from private individuals to state-funded bodies” (Hjort 2012, 12). The Centre also launched schemes for funding young filmmakers’ projects, and in 2014 it introduced the Lithuanian Film Tax Incentive “as a new policy measure to foster local and foreign film production in Lithuania” [10]. These positive developments led to a steady increase of documentary production volumes, with a peak of 22 premieres in 2018. [11] A similar trend was observed across Eastern Europe, especially in Poland (Milla 2017, 32). International film festivals held in Lithuania, namely the Vilnius Documentary Film Festival, the Human Rights Documentary Film Festival Inconvenient Films, the Vilnius International Film Festival Kino pavasaris and the European Film Forum Scanorama did their best in promoting Lithuanian documentaries at home and abroad, providing visibility to newcomers’ films. As Hjort points out, films “are made and seen in contexts that are structured by policies, laws, regulations, and the activities of individuals working for a wide range of film bodies and institutions” (Hjort 2012, 11). The vibrant documentary ecosystem gave stimulus for a new generation of documentarists (currently in their thirties and forties) to make the first steps and build their profiles in the documentary milieu (namely, Giedrė Benoriūtė, Oksana Buraja, Linas Mikuta, Mindaugas Survila, Jūratė Samulionytė, and Giedrė Žickytė), and allowed great directorial feature-length debuts of directors such as Olga Černovaitė (Drugelio miestas / Butterfly City. 2017), Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė (Rūgštus miškas /Acid Forest. 2018), Aistė Žegulytė (Animus Animalis (Istorija apie žmones, žvėris ir daiktus) / Animus Animalis (A Story About People, Animals and Things). 2018), Vytautas Puidokas (El Padre Medico. 2019) and Marija Stonytė (Švelnūs kariai/ Gentle Warriors. 2020), which were internationally screened at various film festivals.

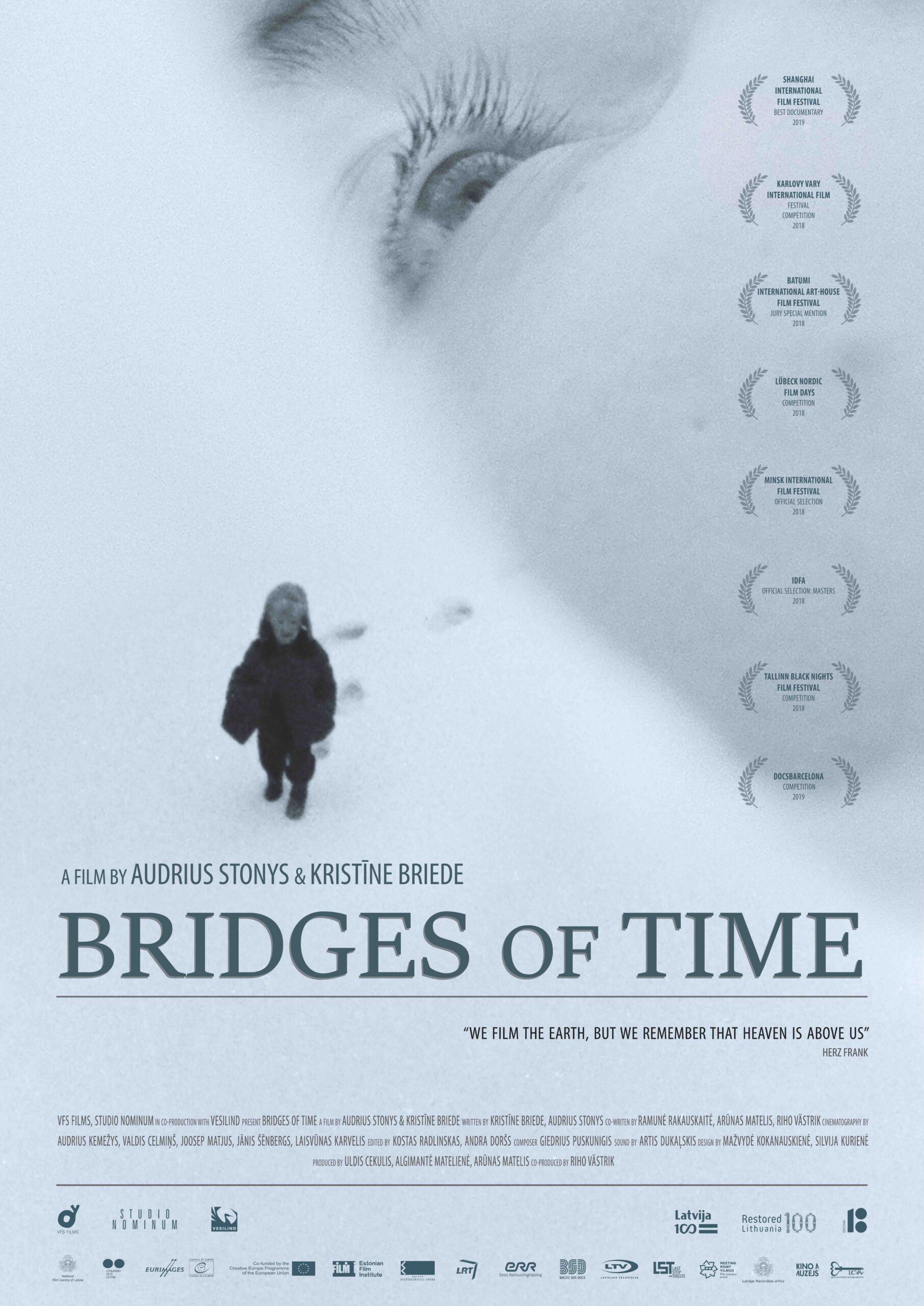

It is worth noting that Lithuanian documentary production companies have always been small in size and have engaged with 1-3 feature film projects at a time. The average budget of a local feature documentary is between 80,000 and 500,000 Euros, which is quite small in comparison with budgets of documentary films in larger and wealthier countries of the European Union. This is because of the modest subsidies for film and of the small linguistic market, as well as the negligible private funding and support by local broadcasters. Therefore, Lithuanian documentary filmmakers depend very much on public funding, co-production with foreign companies and pan-European film support, such as the MEDIA Programme of the European Union and the The European Council’s Eurimages fund. These unfavourable circumstances triggered local filmmakers to focus on creative documentaries made with foreign co-producers, aimed at international film festivals, forums and arthouse cinemas, instead of producing content for public or private television broadcasters. The European Council’s study on Film Production in Europe. Production Volume, Co-production and Worldwide Circulation revealed that Lithuania is one of “the few countries in which co-production of documentaries was higher than that of fiction films”, while “at the European level, 22% of the feature fiction films were co-productions between different countries, compared to 16% in the case of feature documentaries” (Milla 2017, 36). One of the first big scale international co-productions with successful transnational distribution was The Bug Trainer (Vabzdžių dresuotojas. Donatas Ulvydas, Linas Augutis, Marek Skrobecki, and Rasa Miškinytė, 2008), a biopic which told the story of a forgotten pioneer in puppet animation and one of the greatest film geniuses, the Polish-Lithuanian Ladislas Starevich (1882–1965), whose career path started in Lithuania and developed in Russia and France. Produced by the Lithuanian studio Era Film in co-producton with Se-ma-for Film Production (Poland), NHK (Japan), AVRO (The Netherlands), YLE Co-productions (Finland) and supported by The MEDIA Programme, the film was premiered at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, competing in the documentary program section, and was subsequently screened at many other prestigious film venues. Lithuanian documentaries directed by acclaimed auteurs have been also supported by the Eurimages Fund. One of the few successful applicants in 2017 was Bridges of Time (Laiko tiltai. 2018), a film about the Baltic poetic documentary tradition, which flourished from the 1960s onwards, codirected by the Lithuanian Audrius Stonys and the Latvian Kristīne Briede and coproduced between Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. Another submission granted the support of the fund in 2021 was Irena (planned to tell the story of Irena Veisaitė, an internationally acclaimed Lithuanian intellectual, who is the only one in her family who survived the Holocaust). The film will be produced in coproduction between Lithuania, Estonia, and Bulgaria, directed by Giedrė Žickytė. [12] These cases show how filmmakers from a small national market manage to get transnational support and distribution to films with stories of national thematic references, due to well-developed transnational forms of collaboration. The risky, small-nation context thus becomes an opportunity for small-nation documentarists to tell unique local/regional stories to a global audience.

Contemporary Lithuanian documentary film has had several individual success cases internationally, despite of the above described difficulties, caused by the market size and the periods of political and economic transformations. Its first major award after the separation from the Soviet Union was a Felix award of the European Film Academy for the Best European Documentary film in 1992, granted for the short documentary Earth of the Blind (Neregių žemė. Audrius Stonys, 1992) – a reflection on the existence of the visually impaired. This success was followed by other prestigious awards, for example a Short Film Award at the International Documentary Film Festival Cinéma du Réel in 1997 and the main prize at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen in 1998 for Spring (Pavasaris. Valdas Navasaitis, 1997); a Silver Wolf Award in 2005 for Best Mid-Length Documentary at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, a Golden Dove award at the DOK Leipzig Festival, and the 59th Directors Guild of America Award for the Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Documentary for Arūnas Matelis‘Before Flying Back to the Earth (Prieš parskrendant į Žemę. 2005); Yo no soy de aquí (I’m Not From Here. co-directed by Giedrė Žickytė and Maite Alberdi, 2016) nomination for the Best Short Film Award at the European Film Academy Awards in 2016; Bridges of Time (Laiko tiltai. co-directed by Audrius Stonys and Kristīne Briede, 2018) at the Shanghai International Film Festival won Golden Goblet for the best documentary in 2019. The most recent success was Giedrė Žickytė’s Jump (Šuolis. 2020), which was widely screened at international film festivals and received the award of the Best Documentary Feature at the Warsaw International Film Festival in 2020. These examples show that Lithuanian documentary films and filmmakers are well accepted and respected at the international film milieu.

In the last decade Lithuanian documentaries proved that the stories they tell are appealing not only to audiences of international festivals, but to local people as well, receiving relatively high domestic admissions on television and in cinemas. A wildlife documentary The Ancient Woods (Sengirė. Mindaugas Survila, 2017), which was premiered at the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam, broke national records by being the most popular documentary film in Lithuanian history, attracting 67 thousand viewers in cinemas in 2018. Other domestically successful documentaries include Arvydas Sabonis 11 (Rimvydas Čekavičius, 2014), viewed by 39.5 thousand in 2014, Rūta (Ronaldas Buožis, Rokas Darulis, 2018) with over 29 thousand viewers in 2018, and The State Secret (Valstybės paslaptis. Donatas Ulvydas, 2019) with more than 40 thousand admissions in 2019. [13] In view to the above, it can be concluded that modest film funding has not stopped Lithuanian documentary makers in their ambitions to create a vibrant community and connect with local audiences, as making good films requires much more than large populations and enormous financial resources. It needs a unique historical and cultural experience, a rich and expressive language, and talent. Actually, the latter in combination with a clear cinematic vision and high professionalism and dedication of the filmmakers precondition the emergence of films of extremely high artistic quality, even during economically unfavourable and risky times for the industry.

Main documentary directions and directors after 1990

As a next step, I will discuss the main directions of the contemporary Lithuanian documentary film by focusing on the most distinctive films of the two generations of documentary makers, taking into account existing national and global influences on the filmmaking practices, main thematic-stylistic trends, and the way of circulation in the audio-visual market. The post-1990 [14] Lithuanian documentary film can be roughly divided into three generations: the documentarists of the political transformation (who started their careers at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s); documentarists who entered the film industry at the time of Lithuania’s accession to the European Union (May 2004) and beyond; and, finally; the youngest generation (who debuted in the last few years). The close look into the documentary films produced in these periods reveal a clear link between the cinematic form and style and a certain socio-political and economic situation of the state in which filmmakers produce their oeuvres. Similar links were observed and analysed by Michael Renov (Renov 1993), Gilles Deleuze (Deleuze 2009, 2010), Hamid Naficy (Naficy 2001), Ackbar Abbas (Abbas 1997), and Fredric Jameson (Jameson 1995), who coined the theoretical concept geopolitical aesthetic for explaining interrelations between art form and the nation state. While Mette Hjort in her research about the intersections of risk and film proposes a slightly broader perspective of cinematic style analysis, which incorporates the concepts of “individual” and “collective”: “the concept of style can be thought of as encompassing, among other things, choices reflected within a given film, across a number of films, within a single practitioner’s oeuvre or across the oeuvres of practitioners who are deemed to have something in common – the circumstances under which they work, for example, or their commitment to certain values” (Hjort 2012, 9).

Lithuanian poetic documentary tradition and the generation of the 1990s. The community of Lithuanian documentarists is small, but diverse regarding thematic and stylistic choices. The style of the first generation was influenced by the Lithuanian poetic documentary of the 1960s and 1970s, best represented by Algimantas Dausa, Almantas Grikevičius, Robertas Verba, Henrikas Šablevičius, and some others. The oeuvres of these filmmakers are characterized by the “ethnographer’s paradigm” [15], minimal verbal expression, rich visual metaphors employed for telling stories about the everyday routine and celebrations of ordinary people, predominantly villagers, in Soviet Lithuania. They reject to address topics promoted by Soviet nomenclature, as well as voice-over narration, which prevailed the official documentary. This creative strategy was chosen very purposefully to nurture “an alternative documentary discourse to the one developed by the official (favoured) Soviet documentary-makers” (Šukaitytė 2015, 321), and to diminish the risk of censorship and being “shelved”, while addressing “non-heroes” and “non-champions”.

When looking into the documentaries of the newcomers of the junction of the 1980s and 1990s, (Šarūnas Bartas, Arūnas Matelis, Valdas Navasaitis, Audrius Stonys), several things stand out: first, their willingness to work with emerging cinematographers Vladas Naudžius and Rimvydas Leipus; second, a keenness to employ a poetic filter while telling stories about real life, real people and their feelings; and third, their claim to truthfulness without any ambition to tell the viewer the inclusive truth in an explicit way. Though diverse, most of these works share a common stance of respect towards and detachment from their subjects of enquiry, as well as similar stylistic choices, like static shots, deep focus, long takes, slow camera motion, synchronous sound, and the like. Notable films include In Memory of a Day Gone By (Praėjusios dienos atminimui. Šarūnas Bartas, 1990), Ten Minutes Before Icarus’ Flew (Dešimt minučių prieš Ikaro skrydį. Arūnas Matelis, 1990); The Autumn Snow (Rudens sniegas. Valdas Navasaitis, 1992) and The Earth of the Blind (Neregių žemė. Audrius Stonys, 1992). These documentaries reveal real lives, feelings, and document individual and collective experiences of humans in the times of radical political-economic changes. Similarly, as the generation of the 1960s-1970s, they use a strategy of an “aesthete-ethnographer” for documenting, revealing and analysing marginalized societal groups and cultural phenomena. The films of both generations lack a strong social or political engagement, criticism, or mission to shape a viewer accordingly. However, as Jane Chapman puts it, “when the culture that emerges from the pro-filmic content is different to the filmmaker’s culture, then politics of difference – ethnic, class, gender – emerges (…)” (Chapman 2009, 35). These filmmakers aim at building a discourse about a sense of instability and vulnerability, temporality, and the loneliness of people in certain times and circumstances. The films of both generations have often been introduced at international film festivals and thematic film screenings under the umbrella term poetic documentary, referring to the similarity of cinematic strategies as well as a historical, conceptual and aesthetic framework within which the discourse of being is constructed and developed.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the rise of talented young Lithuanian documentarists and their immediate international recognition by the international film community was symbolic, as it happened alongside with significant social, cultural, and political changes taking place in the country at that time. These were the first years of regained Lithuanian statehood, hence, the revival of national cinematography on the world’s map after 50 years. However, only a few filmmakers could survive the times of “wild capitalism” and political-economic transformations without damaging their careers, namely Stonys (European Film Academy Felix winner for the Best European Documentary in 1992) and Matelis (Grand Prix winner at the 37th Oberhausen in 1991), who managed to get prestigious international awards for their first films. [16] International awards [17] gave these filmmakers creative security and freedom of choice to be elitist and keep the creative standards required by prestigious international film festivals, rather than following market demand to be entertaining, socially and politically engaging, and informative. Stonys, for example, in almost his entire oeuvre talks about metaphysical questions of life through a slow flow of images, excluding words and texts, and in this way inviting the spectator to reflect and meditate (such as Viena / Alone. 2001; Uku ukai / Ūkų ūkai. 2006; The Woman and the Glacier / Moteris ir ledynas. 2017). Matelis’s most acclaimed film, Before Flying Back to Earth, talks about the refusal of children suffering from leukemia to give up, demonstrating the filmmaker’s talent and sensitivity to tell a complex story without being sentimental or manipulative. His most recent film, Wonderful Losers: A Different World (Nuostabieji lūzeriai. Kita planeta. 2017) was one of the most awarded and internationally distributed films of 2017. It brings the viewers into the hidden world of the professional cycling sport, avoiding sensations, unlike most films about professional sports and sport elites. Instead scandals, he focussed on marginal (but important) characters of the prestigious Italian Grand Tour Cycling race, Giro d’Italia: cyclists (the so-called “Gregarios”, helpers, etc.), who remain invisible to the public and agree to make personal sacrifices for the victories of the other team members. Even though the film focused on a transnational event and transnational characters, Matelis remained faithful to insightful stories about marginal, eccentric, selfless, but strong willed people. The transnational significance of the film indicates the involvement of eight co-producers: Lithuania, Italy, Switzerland, Latvia, Belgium, UK, Ireland and Spain. Despite of the astonishing achievements of Stonys and Matelis, their obvious dominance in the Lithuanian documentary milieu (caused by small film funding) created “the risk of mono-personalism” and “the risk of exit” (Hjort 2015, 53), to use the terms of Mette Hjort for describing the situation when national cinema is being dominated by exclusive filmmakers, while other talented filmmakers (i.e. Valdas Navasaitis and Algimantas Maceina) with less international success have to exit the field or waist their talent.

New documentary and new generation after 2000. Filmmakers who entered the film industry at the time of Lithuania’s accession to the European Union in 2004 and beyond, came of age in a culturally and socially diverse environment guided by market economy, where film was perceived not just as art, but as creative industry as well. Therefore, for them it was clear that “consumer entertainment is an important aspect of the business of filmmaking, even in documentary” (Aufderheide 2007, 5), especially when films need intermediaries (broadcasters, distributors, sales agents) to secure the production budget and the audiences. According to Hjort, students at film schools “are inevitably taught to think about the tensions between the kind of artistic risk taking that informs and drives personal filmmaking and the risk-aversive tendencies of the film industry in which the film school graduate will eventually have to make his or her way” (Hjort 2012, 14). Most of the graduates of the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre, Film and TV Department in the 2000s joined the creative teams at public and private TVs, advertisement and communication companies, or built their portfolios periodically assisting national and international film production crews; therefore, their knowledge about different audiovisual business models, genres and styles was more diverse than that of the previous generation. Funding for films has been steadily growing since 2006 (with a significant increase in 2018), new funding schemes have been introduced (i.e. Debut Films, Minor Co-productions, Short Film Debut, etc.), and the Lithuanian Film Centre was founded in 2012 – all these increased the possibility for more directors (especially female) to debut with their films. Self-trained film directors (i.e. Mindaugas Survila, Mantas Kvedaravičius) and filmmakers from non-Lithuanian ethnic backgrounds (i.e. Oksana Buraja, Olga Černovaitė, Jonas Ohman, Marat Sargsyan) were getting funded more frequently as film producers with the rise of the need for new cinematic voices, while newcomers in the field also took bigger risks with topic choices.

Since the 2000s documentary has become an important representational practice for women. Several female directors entered the documentary field (Giedrė Beinoriūtė, Oksana Buraja, Inesa Kurklietytė, Agnė Marcinkevičiūtė, Živilė Mičiulytė, Ramunė Rakauskaitė, Jūratė Samulionytė, Marija Stonytė, Aistė Žegulytė, Giedrė Žickytė) due to more available funding and the increased number of female students graduating as film directors. An important role of young female producers – Živilė Gallego, Jurga Gluskinienė, Ieva Norvilienė, Asta Valčiukaitė, Dagnė Vildžiūnaitė and many others – in bringing more women documentarists into the national film industry is also worth mentioning. Female filmmakers noticeably brought a bigger thematic diversity to Lithuanian documentary by addressing problems of poverty and social exclusion, collective traumas and taboos, social urban conflicts, security and the Lithuanian Armed Forces, the relationship between humans and animals, and alike. Female directors have discovered new points of view about Lithuanian history and society and presented the voices of ethnic minorities, children and women, unheard earlier. They took their viewers on emotionally diverse journeys (due to a creative mixing of cinematic styles and forms), strengthening the documentarists’ connection with the audience. Some of their films deal with female identity, motherhood and the place of women in society (for instance, Kristina Kristuje. Inesa Kurklietytė, 2005; Cuckoos Children / Gegučių vaikai. Inesa Kurklietytė, 2012; 7 Sins / 7 Nuodėmės. Kristina Inčiūraitė, 2010; Master and Tatyana / Meistras ir Tatjana. Giedrė Žickytė, 2015), although not evolving into a feminist documentary wave or movement. It should be noted that in the 1990s there were only few female directors, namely Janina Lapinskaitė, Diana Matuzevičienė and Ramunė Kudzmanaitė. Lapinskaitė was the most established documentarist, renowned for her distinct style (based on the combination of fiction and documentary components, performative, observational, interactive, poetical styles and voice over), which was exceptional in Lithuania at that time, despite the global phenomenon of the new documentary, associated by Jane Chapman with the rejection of “the boundary distinction of traditional documentary modes” (Chapman 2009: 97), the fall of the popularity of Direct Cinema, and the increase of “the range of documentary possibilities and the hybrids” (Chapman 2009, 18). As professor at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre and head of the Film and TV Department for more than a decade, Lapinskaitė has also had a big influence on the younger generation of filmmakers.

Oksana Buraja and Jūratė Samulionyė, former students of Lapinskaitė, have a similar approach to documentary filmmaking, which fits the concept of the new documentary. Their films prove that “documentary is always a complicated form of representation” (Chapman 2009, 97) and that “documentaries no longer simply document what is in front of the camera. (…). The hunger for reality and theatricality are two sides of the same coin” (Knudsen 2006, 81). Samulionytė has obvious talent for making documentary films about serious social and political issues without overdramatization or the aim to shape the opinion of the spectators. By employing an empathic approach to social actors and their problems, light irony, playful visual narrative, stressing the theatricality of her characters, as well as being present herself as the filmmaker, her documentary stories become engaging and enjoyable, but avoid being banal. Shanghai Banzai (Šanxai banzai. 2010) is one of several good examples, in which the filmmaker investigates an old, mysterious neighbourhood in the centre of Vilnius, called Šnipiškės, inhabited by a low-income multi-ethnic community. In 2011 Shanghai Banzai won the Grand Prix at the New Baltic Cinema section at the European Film Forum Scanorama. Buraja’s cinematic style is remarkable in mixing components from different documentary and fiction genres (i.e. mystery, drama, social problem, comedy) and the combination of performative, observational, interactive and poetic modes. She focuses on marginal and vulnerable subjects, however, predominantly from the Russophone community, with whom she managed to establish a very close contact, based on mutual trust. In her directorial debut Mother (Mama. 2001), the camera closely observes several small, dirty children in an untidy kitchen, examining the empty shelves of a cupboard, in the hope to find some food, while playing with cockroaches. The film director very subtly creates the image of

an invisible mother. This film collected several international awards, including the Grand Prix in Digital Competition at the Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival in 2002, and Special Mention at the Oberhausen Short Film Festival in 2001. In Lisa, Go Home! (Liza, namo! 2012) – another film that was welcomed favourably at the international scene – the director focuses on a little rebellious girl, growing up in a family exposed to social risk. The miserable and toxic life of adults (shot in an observational style) is seen through the eyes of a girl who finds escape from depressing reality in nature (shot in poetical mode), where she hides herself for hours.

Poverty, social segregation and precarity are a widespread phenomenon in Lithuania, and an increasing number of (predominantly young) documentarists started to engage with these problems, especially beginning with 2010 (i.e. River / Upė., Julija Gruodienė and Rimantas Gruodis, 2009; Shanghai Banzai, 2010; Through Fire I Went, You Were With Me / Aš perėjau ugnį, tu buvai su manim. Audrius Stonys, 2010; The Field of Magic / Stebuklų laukas. Mindaugas Survila, 2011; Father / Tėvas. Marat Sargsyan, 2012; Lisa, Go Home! 2012; Dinner / Pietūs Lipovkėje. Linas Mikuta, 2013; Dzukija‘s Bull / Dzūkijos Jautis. Linas Mikuta, 2013; Lucky Year / Sėkmės metai. Rimantas Gruodis, 2014; Dead Ears / Šaltos ausys. Linas Mikuta, 2016; Roman’s Childhood / Romano vaikystė. Linas Mikuta, 2020). Although it is difficult to explain all the reasons for the proliferation of films about poverty, one likely factor is the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, which hit Lithuania very strongly. The situation was aggravated by aggressive austerity measures implemented by the Lithuanian Government in 2008 and 2011, including cuts in social expenditures, pensions, and family and unemployment benefits.

The producers of social theme documentaries clearly take sides. The point of view is that of the social actors: farmers, unemployed or retired people, and others coping with poverty on a regular basis. Filmmakers make sure that their voice is heard and that they are represented with respect. As a consequence, the observational technique prevails in these type of films. For instance, Linas Mikuta in all his films closely looks into the lives of marginal people in rural and urban environments and explores the phenomenon of the culture of poverty which, according to anthropologist Oscar Lewis is a “design of living which is passed down from generation to generation” (Lewis 1963, xxiv). In the most recent of his films, Roman’s Childhood (with was premiered at DOK Leipzig Festival’s International Competition programme in 2020) he observes a family at the margins of society, with an eight-year-old boy living in a non-domestic building in a Lithuanian harbour city. The camera focuses on the boy and his sincere relationship with both parents. The filmmaker avoids commentaries, judgements and sentiments, instead, he focuses on family values and the will to remain together in the times of hardship. Mindaugas Survila has a similar approach towards his characters. His documentary entitled The Field of Magic takes an empathetic, respectful, and convincing look at homeless people, whose temporary home has been Buda wood for several years, and workplace the Kariotiškės dump near Vilnius. The representation of homeless is completely different compared to those seen on TV or photo reportages. In Survila’s film they work, cook, pray, cut their hair, cry, love, and do other things that people usually do. The Field of Magic was developed at and produced by the studio Monoklis, where it benefited from considerable support from documentary filmmaker Giedrė Beinoriūtė and producer Jurga Gluskinienė. Several film festivals, including Toronto, Doc Point, and Hot Docs, have included this film in their prestigious programs. Apparently, the film was one of the biggest discoveries of the year 2011, together with Mantas Kvedaravičius’ Barzak, 2011, as both films were outstanding directorial full length documentary debuts of directors without a professional training.

According to historian Jerome De Groot, the representation of history and historical narratives has become a significant part of popular entertainment, including a wide range of cultural phenomena, such as museums, TV programmes, games, fiction and documentary films (De Groot 2009). The historic turn is also noticeable in Lithuanian documentaries made in the 2000s. Starting with Giedrė Beinoriūtė’s Grandpa and Grandma (Gyveno senelis ir bobutė. 2007), history has become an important topic in Lithuanian female creative documentaries. A subjective, personal approach is used to tell about the mass deportations and the genocide of Lithuanians during Stalin’s ruling in annexed Lithuania. This became a certain guideline for other filmmakers working with collective memory and collective trauma issues. The film narrative is constructed from a voiceover commentary of a girl (who speaks on behalf of the film director to give an impression of the way in which the grandparents’ painful experience was seen by the film’s author when she was young), animated images, archival footages and family photos. Other remarkable documentaries which use a similar strategy for talking about national history, are Martina Jablonskytė’s essay film Lituanie, my freedom (Lituanie, mano laisve. 2018) and Jūratė Samulionytė’s work codirected with her sister photographer Vilma Samulionytė, Liebe Oma, Guten Tag! (Močiute, Guten Tag! 2018). Jablonskytė tells a story of diplomatic and physical battles that preconditioned Lithuania’s independence in 1919 and raises questions about the meaning of freedom for the young generation of Lithuanians and Europeans, and about the difference between territorial and personal freedom. The Samulionytė sisters in their film try to break national taboos – the topics of suicide and the destinies of Lithuanian Germans after World War II, inspired by the life of their German grandmother Ella Fink and the experiences of her family who lived in the East-West Lithuania. The film directors are the main narrators and investigators of the life of their grandmother, which is little known to them. They are also the characters of the film, together with their parents and other family members living in Lithuania and Germany, whose memories and reflections help to reveal hidden truths and dramas of their family and the German minority in Lithuania. The film was very well received by Lithuanian and international audiences.

Lithuanian filmmakers frequently exploit old archival footages and photos in their historical documentaries. However, films, that are fully based on archival footage, known as compilation films, are not very common. A leading filmmaker of historic compilation films in Lithuania is Giedrė Žickytė, whose films deal with the Soviet period of Lithuanian history, culture and art. Her films mirror the collective memory of the nation in times of oppressive regime. Žickytė is one of the internationally most successful Lithuanian female directors. She debuted in 2009 with a TV movie Baras, which received the Best TV Film award at the Lithuanian Film Awards in 2009. In her second film – a playful documentary about the Lithuanian Singing Revolution at the end of 1980s and the beginning of 1990s, How We Played the Revolution, (Kaip mes žaidėme revoliuciją. 2012) – she demonstrates her outstanding talent in telling a complex story through a large amount of carefully selected and interlinked archival footage. Since then, all her documentaries about recent Lithuanian history (i.e. Master and Tatyana / Meistras ir Tatjana. 2015; The Jump / Šuolis. 2020) where compilation documentaries of great aesthetic value and of vast appreciation by international audiences. Throughout her entire oeuvre, Žickytė develops historical narrative from national and international historical contexts and individual, personal stories. All her films received prestigious national awards and theatre distribution in Lithuania. They were picked regularly by international film festivals, including the Warsaw International Film Festival, Rotterdam International Film Festival, Sheffield Doc/Fest, Bergen International Film Festival, Trieste International Film Festival and many others. Žickytė’s documentaries undoubtedly integrate Lithuanian stories about the Soviet past into transnational discourses about post-colonialism and the Cold War and help international audiences to learn about Lithuanian and European history in an attractive and engaging way.

According to Aufderheide, the nature documentary became a major subgenre and “an established part of the broadcast schedule”. Films about wildlife, environment and similar topics are not ideologically neutral, as they disseminate certain models of relationship with our environment (Aufderheide 2007, 117). The interest of young Lithuanian filmmakers in nature or environmental film has also visibly increased during the last decade and can be explained by a globally growing appeal for wildlife and climate change films on big screens, audiovisual content platforms and platforms enhancing environmental activism. One of the most prominent films of this genre in Lithuania is undoubtedly Mindaugas Survila’s Ancient Woods (2017), which immerses the viewers into the mysterious, funny and slightly intimidating world of Lithuanian ancient woods. It is with great passion and patience that Survila worked for more that eighteen years on this film. The documentary received wide national and international appeal and grossed more than 60 thousand Euros, which was invested in expanding and preserving ancient woods in Lithuania. Moreover, Survila launched Ancient Woods Fund for the same purpose, [18] which accepts private donations. This type of film activism is phenomenal on the national scale. Other filmmakers – Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė (Acid Forest / Rūgštus miškas. 2018), Marija Stonytė (One Life / Vienas gyvenimas. 2019), Aistė Žegulytė (Animus Animalis (A Story About People, Animals and Things / Animus Animalis (Istorija apie žmones, žvėris ir daiktus). 2018) invite the audience to rethink their relationship with animals and the environment in the Antropocene, an epoch in which human egocentric behavior is causing irreversible environmental damage. These films express explicit, however subtle criticism of the consumerist approach to nature and animals.

These observations of the films made by new generations of Lithuanian documentarists reveal a certain conceptual shift in the milieu of professional filmmaking. That milieu seems to have recognized a point that Graeme Turner made about film in a more general context, in connection with certain shifts that he sees as desirable: filmmaking “is not essentially an aesthetic practice; it is a social practice which mobilizes the full range of meaning systems within the culture,” (Turner 2006, 236) inasmuch as “we can locate evidence of the ways in which our culture makes sense of itself” (Turner 2006, 4) in the stories filmmakers tell. As Turner suggests, seeing filmmaking in this light marks a shift away from well-established paradigms, and is also a precondition for a new reconnection of “films with their audiences, filmmakers with their industries, [and] film texts with society” (Turner 2006, 236).

Conclusion

My critical overview of the main directions in contemporary Lithuanian documentary suggests that the Lithuanian documentary film ecosystem was “risk intensive” and “risk wide” in the 1990s and the first decade of 2000s, [19] due to the political and economic instability caused by a fast and harsh transition from a socialist to a capitalist regime, a cultural isolation, and insufficient private and state investment into production and infrastructure. This systemic risk evoked the danger that the local documentary milieu would be dominated by a few internationally successful film directors, certain topics and film styles. In such an environment characterized by risk and a shortage of resources, survivors were the ones who accumulated significant symbolic capital (prestigious international awards) and fitted into the canon of the national poetic documentary. Others had to exit the film milieu. Lithuania’s membership in the European Union and its smooth integration into the European audiovisual market was followed by the local political reform of the film sector in 2011-2012, which in turn contributed to the boom of documentary production, including international co-productions and the rise of a new generation of documentarists. The increased support from the state and the entrepreneurial spirit of the new generation of producers resulted in a bigger stylistic and thematic diversity within the national documentary genre. In the 2000s the rate of female directors clearly increased, and the same is true for directors with non-Lithuanian ethnic background or directors without formal film training. These changes, together with the arrival of the new documentary philosophy, have shaped the Lithuanian documentary: while earlier it was a form based on ethnographic and poetic representations (closely connected to the national tradition of 1960s and 1970s), now it turned into a hybrid, personal and performative genre. Still, the poetic documentary tradition remained vibrant, while compilation (archival) documentary gained popularity. Lithuanian documentaries proved that the stories they tell are appealing not only to audiences of international festivals, but also to local theatres, with high admission rates. Risks typically associated with small markets are diminished partly by a growing number of international co-productions, and partly following the global trend: the rising popularity of documentaries.

[The Hungarian version of this article is published in this same thematic issue]

Jegyzetek

- [1] EUROSTAT data on EU population in 2020. Accessed July 10, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/11081093/3-10072020-AP-EN.pdf/d2f799bf-4412-05cc-a357-7b49b93615f1 ↩

- [2] STATISTA data on Gross domestic product at current market prices of selected European countries in 2020 (in million Euros). Accessed July 10, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/685925/gdp-of-european-countries/ ↩

- [3] Lithuania was overruled by Russian Empire (1795–1914), Soviet Union (1940-1941; 1944-1990), Germany (1941-1944), The Western part of Lithuania was a part of the Kingdom of Prussia for centuries while Vilnius county was annexed by Poland (1919-1939). Source of information: Lithuanian encyclopaedia. Accessed July 10, 2021. https://www.vle.lt/ ↩

- [4] In this article I apply Wilma De Jong’s definition of creative documentary as “a hybrid film genre which attempts to represent the ‘real’ in a creative and critical art form”. (De Jong, 2011:20). To this definition I add one more criteria – recognized/approved as “creative”, “innovative”, “artistic” by prestigious international film festivals and art institutions (museums, film institutes, etc.) as well as creative documentary distribution channels alike „ARTE TV“, „Sundance TV“, „Channel 4“. ↩

- [5] European Audiovisual Observatory, data on World Film Market Trends. Accessed July 10, 2021. https://www.obs.coe.int/en/web/observatoire/industry/film?p_p_id=101_INSTANCE_NTHRA9ube66y&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-4&p_p_col_count=1&_101_INSTANCE_NTHRA9ube66y_delta=10&_101_INSTANCE_NTHRA9ube66y_keywords=&_101_INSTANCE_NTHRA9ube66y_advancedSearch=false&_101_INSTANCE_NTHRA9ube66y_andOperator=true&p_r_p_564233524_resetCur=false&_101_INSTANCE_NTHRA9ube66y_cur=5 ↩

- [6] Source of information: Lithuanian encyclopaedia. Accessed July 10, 2021. https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/lietuvos-ekonomika/ (Note: the conversion of the currency is done by the author of this article). ↩

- [7] The Studio Kinema emerged as a new site of production for a new generation of filmmakers (Audrius Stonys, Artūras Jevdokimovas, Rimvydas Leipus, Valdas Navasaitis, among others), who, much like their peers in other Eastern or Central European countries, were rebelling against the old, centrally controlled film production system. Thanks to his talent and luck as entrepreneur, Bartas managed to fund films that his studio produced with money derived exclusively from private and foreign sponsors. Equally significant was Bartas’ approach as producer: young filmmakers were allowed to shoot what and how they wanted, with the full support of the studio. Kinema productions achieved international recognition at prestigious film festivals relatively quickly, including at Oberhausen, the Berlinale, IDFA, Karlovy Vary, and Rotterdam. Prizes and nominations allowed the studio to accumulate much needed symbolic capital: Trys dienos (Three Days, Šarūnas Bartas 1991), for example, premiered at the Berlinale and was nominated for the European Felix’92 in the category of Young European film while The Earth of the Blind (Audrius Stonys, 1991) won the Felix’92 for The Best European documentary. ↩

- [8] Based on multiple e-sources. Accessed July 11, 2021. http://www.lfc.lt; http://www.lkc.lt/en/; Baltic Film Facts and Figures https://www.filmi.ee/en/estonian-film-institute-2/facts-and-figures/baltic-films-facts-and-figures ↩

- [9] The full title of the fund is Eurimages, the Council of Europe’s support fund for the co-production, distribution and exhibition of European cinematic works. ↩

- [10] The Lithuanian Film Centre. Accessed July 11, 2021. http://www.lkc.lt/en/tax-incentives/ ↩

- [11] The Lithuanian Film Centre. Accessed July 11, 2021. http://www.lkc.lt/en/lithuanian-film-center/statistics/ ↩

- [12] Eurimages Press Release, Ref.03-2021. Accessed July 11, 2021. https://rm.coe.int/03-2021-163rd-board-of-management-decisions-en/1680a2fd06 ↩

- [13] The Lithuanian Film Centre. Accessed July 12, 2021. http://www.lkc.lt/faktai-ir-statistika/ ↩

- [14] On 11 March 1990, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania adopted an Act on the Restoration of an Independent State of Lithuania. ↩

- [15] According to Hal Foster, ethnographer’s paradigm displaces the problematic of class and capitalist exploitation with that of colonialist oppression, and also the social with the cultural or the ethnographical. (Foster 1996: 174) ↩

- [16] Even acclaimed directors of poetic documentaries, such as Šablevičius, Verba and Edmundas Zubvičius had difficulties securing financing for their films and keep the standards set in their earlier works because of a big instability in the film sector, which brought, as Iordanova accurately puts it, “an increased consciousness of the generational split in filmmakers’ ranks” (Iordanova 2003: 146). ↩

- [17] For example, a Silver Wolf Award in 2005 for Best Mid-Length Documentary at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, a Golden Dove award at the DOK Leipzig Festival and the 59th Directors Guild of America Award for the Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Documentary for Arūnas Matelis‘ Prieš parskrendant į Žemę (Before Flying Back to the Earth, 2005). ↩

- [18] Accessed August 1, 2021. https://www.sengiresfondas.lt/en ↩

- [19] Terms used by Metter Hjort in her article on “The Risk Environment of Small-Nation Filmmaking” (Hjort 2015: 50). ↩

Erre a szövegre így hivatkozhat:

Renata Šukaitytė: Contemporary Lithuanian Documentary Cinema: A Critical Overview of Main Film Directions. Apertúra, 2021. fall. URL:

https://www.apertura.hu/2021/osz/sukaityte-contemporary-lithuanian-documentary-cinema-a-critical-overview-of-main-film-directions/